The Determinist's Illusion

May this series of curated photons agitate your amalgamated neurons.

There are few pastimes I enjoy more than diving into someone else's universe and playing by their rules. Constructing a vision of the world founded upon their logics and rationale, expanding it out to its ultimate conclusion. In playing this game, we glimpse the mind of another. It is not unlike empathy, though to the meager ends of speculation and amusement. Revelation, if we're lucky. When we apply the logics of a belief to parts of the world it was never concerned with, we discover vexing truths: that God is the maker of all things wicked, or that even the act of living is an ethically ambiguous endeavor. There is a twisted joy in unveiling the precarious foundations of convictions that lead to these conclusions. After all, claiming a belief to be true is no trivial matter—it is wise to scrutinize our own truths with the same fervor.

Determinism

The doctrine that all events, including human action, are ultimately determined by causes external to the will. Some philosophers have taken determinism to imply that individual human beings have no free will and cannot be held morally responsible for their actions.

To the determinist, life and all such things that exist are but pieces of effable machinery that math and science can solve and predict with precision. By virtue of cause and effect, and the fact that big things are made of small things that are mathematically explained, all things are thus mathematically explainable. From the cosmos to the mind, all that which is made of calculable things is calculable. And so it stands to reason that all things that behave as such are predetermined. This is a profound realization to have about the world. So profound, in fact, that the determinists themselves do not believe it.

I am no one to claim that people actually believe other than what they claim to, but in the case of the determinist, I must make an exception. Of all the determinists I have ever met and engaged with on the topic, a near-universal response that arises when met with any criticism is a strong adherence to the illusion of free will. They somewhat paradoxically suggest that there is no free will, but that, regardless, you should act as though there is. As if you ever had any choice.

As any decent philosopher ought to do when mulling through the standpoint of another philosophy, one asks questions, even the most basic, such as to establish the precise point of disagreement. So I ready up some questions as though I knew this moment would be:

- "Doesn't a predetermined universe rend itself nihilistic? What could be the meaning of such a world's existence beyond that which is meaningful to something that finds itself outside of it's deterministic confines? For within such a world, meaning itself is not a granted, but determined."

- "What of morality? It is contingent upon the agent's agency. How could you suggest any sense of morality or any better course of action, given that there is no other way the universe could have ever been?"

To these, and more specifically the latter, I receive a response like "just because everything is already determined doesn't mean you shouldn't try to strive for a better world or do what's right." They sometimes even refer to the illusion of free will as being something wholly necessary for the greater good of humanity. One primary example of this is choosing to act as though all guns are loaded, even if they might not be. This leads to a safer way of being for those who engage with them. But this example is more suited to the agnostic determinist. Acting as though all guns are loaded in knowing that it might not be is not the same as wholly adhering to a belief that all guns are in fact always loaded. Thus the loaded gun example pertains more to the idea that free will might not exist, but it is better to assume it does. This small but significant difference is precisely the difference of belief. One states, "There is no free will, but better to assume there is." and the other states, "There may be no free will, but better to assume there is." The only difference is acknowledgment of possibility.

There are some philosophers though, who believe we ought to fully accept we have no free will, and treat everyone as such. It is a method to shed prospects of blame. If we are, after all, by-products of our environment entirely, then would it not be best to simply find solutions to what has been wrought of us rather than to mire someone in blame and guilt for who they are or what they have done? This is a noble approach, if ever I've seen one, but the very notion of suggesting that anyone should do anything is contradictory to their ever-so-logical framework from which they derive their deterministic outlook. It is here, nestled in this particular facet of belief that I see how little the determinist believes in his own idea. Should the determinist hold true belief about the deterministic nature of the universe, he ought to eliminate any such words that refer to the freedom thereof from his regular lexicon. "Should" and any future tenses have no sway over a universe that is already determined. It is odd that anyone who genuinely believes such a thing as determinism ought to care about anything at all. However, a deterministic universe does not render the human experience as any less than it is, only what it has the freedom to be. Any and all efforts toward an end are so because they could not be otherwise, and so too are our successes, downfalls, and tragedies. This means you nor I, nor anyone else have any capacity to change our fate, and that all things both great and terrible must be. All that will be is was.

This leads to a rather strange picture of the universe. If we imagine the present universe as merely a consequence of every previous state of the universe, we can take all of existence, and frame it as a single entity. All of time, having only one possible determined outcome, is itself in its entirety a single state. Even the likes of experience, emotion, and all the qualia entailed with living is but a state of matter. Frameable and definable. Sorrow is no longer part of the ineffable depths of humanity, only a string of neurons through a stretch of time.

Compatibilism

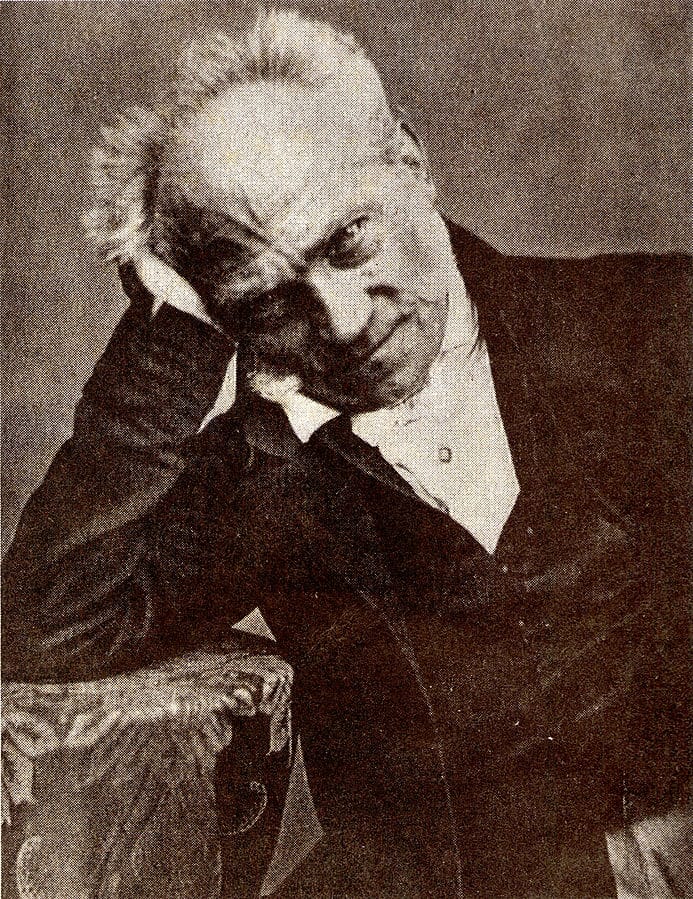

Perhaps I am not giving the determinists a fair shake. Their exists an exceptional flavor of determinist known as the compatibilist. These folk hold that determinism does not preclude free will, but that the two can coexist. This maintains the arguments for moral responsibility while also yielding to the apparent logical consistency of a deterministic universe. To differentiate the two ideas, we can look at a famous saying by Arthur Schopenhauer:

"Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills."

That is to say, what we are compelled by is determined, just as we ascribe the particular motivations any person has to who they fundamentally are. But whether or not they act on these motivations, within that choice, lies their freedom. This ties rather closely to the idea that we cannot choose what to believe. I cannot force you to believe that the sky is any other color than what you believe it to be unless something I say changes your perspective. For example, perhaps I convince you that color is contrived; just experience assigned a name. What you identify as blue, I might identify as red. Or perhaps what you call blue is what I call blue-green. Regardless, you have been convinced and your belief has changed. Belief is therefore apparently changed by something external to the self, an experience that refutes the conclusions drawn through reflection of your previous experiences–if this idea rings incomplete, then you are in good company.

Within our mind lies not only imprinted experiences of the past, but also the ability to ruminate and reflect. This process is somewhat special due to the new experiences we provide ourselves from its enactment. When we reflect, we endeavor to generate new experiences. In solitude, a man can derive something new that has nothing to do with the solitude he is in. Just as the hermit leaves for the mountains and comes back enlightened, so to can you create new experiences that form the foundation for new ideas. I imagine the Buddha's enlightenment had more to do with the experiences he generated within his mind rather than where he sat, after all. Perhaps this generation of experience is due to something like the nature of language—codified meaning that can abstractly be put together to create something infinitely new meanings. But this is still an instance of new experience generated by the self. Are these predetermined too? This is where the compatibilist draws the line. While these determinations— motivations and compulsions—are set to happen, you can choose to act upon what these determinations compel you to do. This is the freedom of the will.

But what is this conclusion but not the determinist in denial? Or is it rather an indeterminist in denial? Does the compatibilist admit the logical persuasiveness of infinite causation? Or does he deny the possibility that he is not free to act as he wills? All things are determined except for where it matters most. Is not the will to act made of the same stuff as the motivation? Are there not causes of action as there are causes of motive? They argue that free will exists at the level where individual make a choice, but who’s pulling the strings of those choices? Motivations— born from experiences, shaped by environment, influenced by genetics, molded by... it’s turtles all the way down. The compatibilist is in a rather precarious position, claiming to agree with contradictory sentiments. To them, there must be an influence by the self removed from causes. Some part that individuates us from causality itself. Something that makes us special.

Could I convince you that the sky is not blue? That it is in truth a myriad of uncolored photons that are but the initial agitator of your photoreceptors that crunch electrical signals for your brain to interpret into its experience of its blueness? Just so, the determinist is convinced that the sky is not blue, that it is all the agitations of neurons called blue. They have convinced themselves that they are not free, that it is all the agitations of neurons called freedom. And yet they persist. They are not free, but they indulge in freedom. They speak on ethics and the better ways of being as though they ever had a choice, as though there is any better future to be had. Their rationale is cemented in a firm way and they speak truths they do not feel. They believe things they do not know and they know things they do not believe.

At the end of it, the determinist too is human and cannot help but be rapt in the throes of living. Experience is an inescapable part of the deal. We will love, hate, rally, and revolt. And so it is that they too cannot help but adhere to the illusion, as that experience is the very essence of our existence. Their illusion is not mine, but our belief is the same.

Thanks for reading, it's my hope that you find in this what I do writing it.

Subscribe for more.

Comments